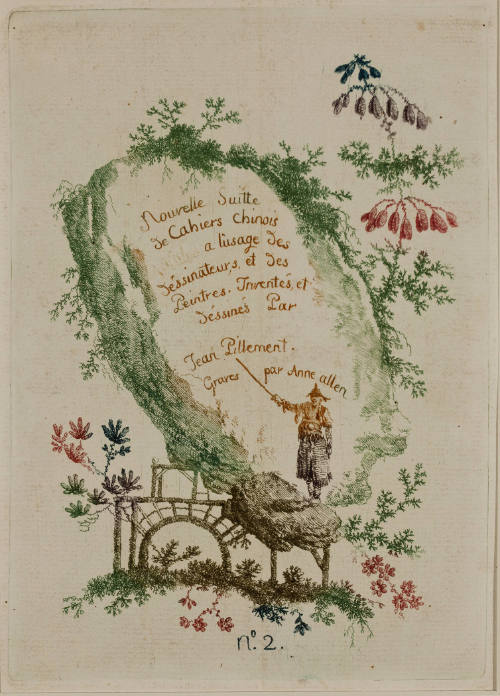

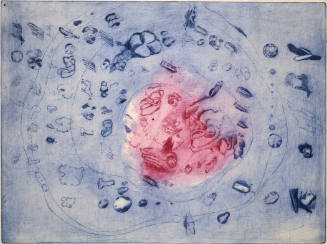

Nouvelle suite de cahiers chinois no. 2

Sheet: 10 1/4 × 9 1/8 in. (26 × 23.2 cm)

Matted: 24 × 32 in. (61 × 81.3 cm)

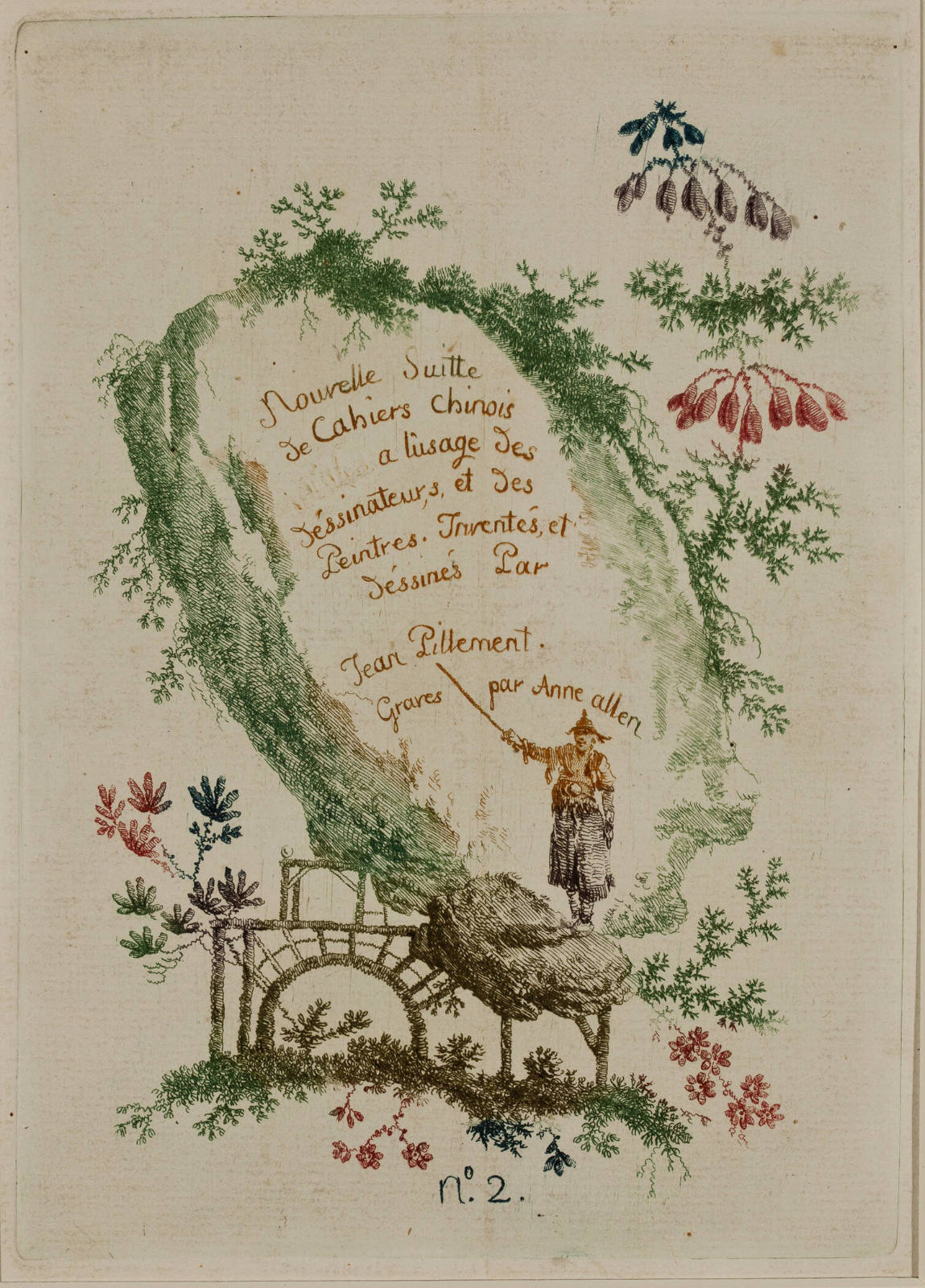

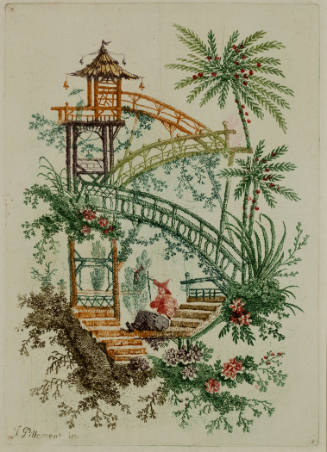

For centuries, European artists incorporated motifs from Asian art in the ornamentation of luxury goods. Then, in the late 18th century, the designs of Jean Baptiste Pillement melded the delicacy of Asian art with the asymmetry of Rococo style. With his primary printmaker, Anne Allen (who was also his wife), he issued nine cahiers, or albums, useful to producers of decorative arts. This one includes fantastic and whimsical designs derived from Chinese sources. Appropriations from Pillement’s designs appeared all over Europe during the following decades, in the form of wallpaper, textiles, porcelain, and furniture. For each of the prints displayed here, Allen applied several pigments one at a time into the incised design to prevent the inks from mixing. Differences in the placement of the inks and the selection of the colors ensured a unique result for each impression of a given design.

Resource: Chelsea Foxwell and Anne Leonard, Awash in Color: French and Japanese Prints, exh. cat. (Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, 2012), pp. 47–49, 80–81.

Chinoiserie is a broad term encompassing the Western craze for all things Chinese that peaked in the 18th century. Europeans were exposed to Chinese goods being brought to market through the various East India trading companies. These exotic luxury imports inspired European imitations that adapted Chinese artistic idioms to local tastes. The result was, as Maria Gordon-Smith has put it, “a utopian vision of Cathay, an escape from things mundane into a joyous world of aesthetically pleasing pseudo-Oriental scenes.”

Anne Allen made three suites of chinoiserie prints after Jean Pillement’s designs, of which this is the second. The Nouvelle Suite de Cahiers Chinois is a tour de force of the subtle color printing process called à la poupée, meaning that the individual colors have been hand-applied to the copper plate with a tool (called a poupée in French) consisting of a stick with a cotton wad at the end. This laborious method caused inks to run together, making for sinuous transitions from one color to another. Colors printed from separate copper plates, on the other hand, did not bleed together since there was time in between for the inks to dry.