Henry Moore

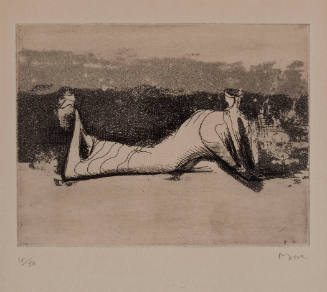

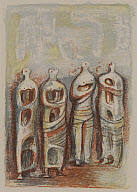

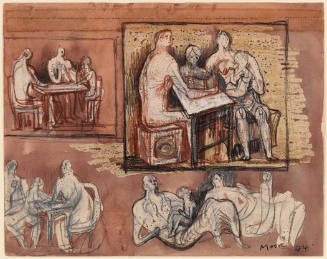

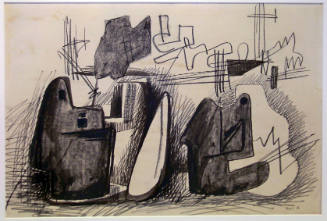

The son of a coal miner, Henry Moore carried remembrances of childhood that presaged his becoming a sculptor—from the imposing (and intriguing) mining companies in his native Yorkshire, to attending Sunday school and hearing a story about the Italian Renaissance painter and sculptor Michelangelo (1475–1564). Early in his career, Moore viewed sculptures as solid, unitary blocks, but by the 1930s he was championing an abstract sculptural vocabulary that included “truth to materials” and “significant form.” He believed these artistic concepts were best achieved through direct carving in stone and wood, although he also worked in cast bronze. Moore introduced holes in the form that actually penetrated the piece, thus uniting the so-called front and back views. Even when engaged in his most abstract work, Moore remained firmly committed to the expressive possibilities of the human figure, explaining, “For me sculpture is based on and remains close to the human figure.” From the end of World War II, he focused on his preferred subject, the figure, and inventively united a modern formalist aesthetic with classical humanistic thought, which incorporated psychological and associative elements.

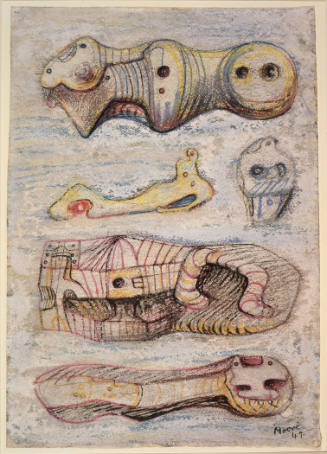

Henry Moore is considered one of the most important British artists of the 20th century, and he twice represented Britain at the prestigious Venice Biennial. Moore was primarily a sculptor but also created many works on paper, which could stand alone or act as models for his monumental sculptures. He had many influences, including the Mayan Chacmool, a type of reclining figure used for burnt offerings, and Michelangelo, whose sculptural figures initially inspired him. Featured here are six works that highlight Moore’s interest in the human form and his fascination with the movement of the sculptural body within its environment.