Setsudo, Joun

Beginning in the mid-17th century, Chinese monks of the Rinzai sect of Zen (in Chinese, Chan) Buddhism immigrated to Japan in a great wave and dramatically altered religious life there. These Buddhist monks were members of the Obaku Zen sect (or Huangbo in Chinese) who were fleeing political disorder at the end of the Ming dynasty (1368–1644). Their unorthodox beliefs—admitting antithetical Esoteric and Pure Land Buddhist doctrine into their Zen practice—made them unwelcome to native Japanese Rinzai monks. The ruling Tokugawa government did welcome them, however, and the exiled monks established their headquarters in Kyoto on land donated by the ruling emperor. Born in Osaka, Setsudo Joun represents the next generation of the Obaku Zen sect, as it became infused with native converts.

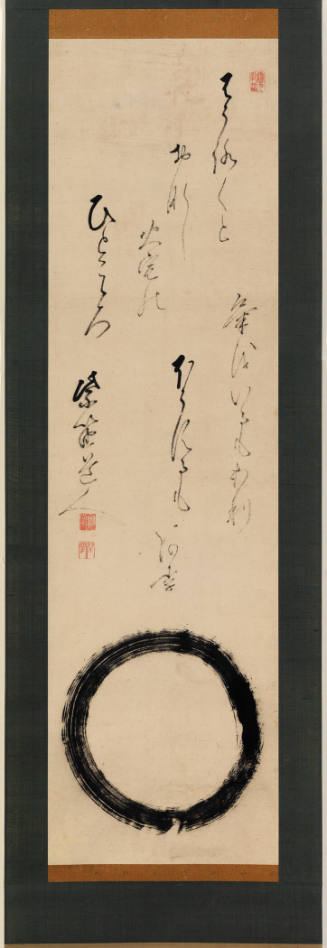

Zen painting and calligraphy (in Japanese, Zenga) was created by devout monks and nuns, rather than by professional artists. These amateurs based their works on the disciplined life of meditation and their search for spiritual enlightenment. Many of the most prominent monks of the Obaku sect were excellent calligraphers and rated the art of fine writing among the accomplishments of a learned monk. Setsudo likewise valued that scholarly tradition and was well known in his day for his brushed texts, many of which accompanied Zen-inspired images.